In 1958, Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo had a solidly crafted script in the thriller/detective genre, but the manner in which the director effortlessly blended a range of genres like the thriller, romance, mystery, horror and drama makes it a fascinating watch. This classic hits 60 this year.

Structurally, like Hitchcock’s other masterpiece Rear Window, Vertigo resembles a thriller, which as a generic term has come to include a wide range of films — detective, police procedural, spy, political thrillers, courtroom thrillers, erotic thrillers or psycho thrillers, that is to say “all films dealing with the perpetration or prevention of crime” sharing another crucial characteristic —suspense.

Generally thrillers focus on plot over character and emphasise intense physical action over the character’s psyche. Psychological thrillers tend to reverse the formula to a certain degree, emphasising the characters just as much. Usually crime thrillers are organised around an innocent victim wrongly accused, here in Vertigo it is Scottie (James Stewart) who unintentionally lands up in a world of intrigue and deceit.

Scottie is here deceived by his own schoolmate Gavin Elster into believing that his wife Madeleine (Kim Novak) has developed suicidal tendencies for he believes that a long-dead maternal ancestress named Carlotta Valdes has come to possess her and lead her to a repetition of the ancestor’s suicide.

Elster takes advantage of Scottie’s acrophobia, the vertigo, a psychosomatic illness, as Elster decides to use him in his plan to murder his wife. Up to a certain point then, Vertigo resembles both the psycho thriller and the crime thriller.

Along with Vertigo Hitchcock started a trilogy of films from this period that would focus on the need to conceal aspects of someone’s disturbed character, the other two being Psycho and Marnie.

We start questioning whether his films focus on obsession or are they exorcisms of those very same and overtly destructive longings for certainty and fantasy.

Unlike the psycho thriller Psycho, or other 1980s or early 1990s film, Vertigo does not show the presence of a stalking “monstrous” (because mentally disturbed) figure, a psycho killer lurking at the centre of the film.

Yet like any psychological thriller, Vertigo indulges in deceptive mind games and delves deeper into the complexity of the human mind and its fatal obsession. Hitchcock, it seems, was obsessively trapped in his dedication to “pure cinema”, a director who was in awe of aberration and yet found it tantalisingly attractive.

Organised around the psychotic effects of a trauma on a protagonist’s current involvement in lone affair and a crime or intrigue, Scottie in Vertigo, is a victim of some past trauma and of a real villain (Gavin Elster), who takes advantage of his friend’s masochist guilt. The villain makes the female protagonist acquire an unaccustomed identity to serve the murderous plot.

Judy acquires the identity of Madeleine, Elster’s wife to dupe Scottie. As Scottie is made to investigate Madeleine’s moves and follow her every where she goes, Scottie’s role is that of a private investigator making this film akin to the detective thriller. Scottie’s frighteningly dark, harrowing and extreme obsession on Madeleine grows.

Abandoning the boyish Midge he falls desperately in love with the possessed woman, only to witness her death when she fakes a spectacular suicide by intentionally leaping into San Francisco bay. He dramatically saves her and brings her to her place. At its greatest moments this “dark and romantic fable” undeniably invokes the mood of the film noir but Vertigo privileges the woman’s story in a way no film noir has ever done before.

Hitchcock stylistically deviates from the genre’s characteristic absorption in the man’s dilemma (falling in love with a villainous woman) and intelligently does away with the typically convoluted plots found in film noirs.

The phenomenal rooftop sequence of Vertigo, the chase and Madeleine’s fall from the rooftop repeated twice in the film make this psycho/ crime/erotic thriller a horror film too.

Interestingly enough, both Vertigo and Hitchcock’s Rebecca tell the tale of a dead (absent/ absence as presence) woman’s grip on a living “daughter” figure.

Kim Novak in Vertigo is a femme fatale, presented as a mysterious and seductive woman whose beauty and charm ensnares Scottie in bonds of irresistible desire leading to Scottie’s insane obsession.Its major focus on Scottie’s romantic obsession for Madeleine, the essential theme of love at first sight, infidelity, the love story and the search for love is at the heart of the film.

Accurately described as a “dark and romantic fable” by Donald Spoto in ‘The Dark Side of the Genius’, its ultimate ending in tragic love make it a romance that may be seen as a sub genre of the drama film. It brilliantly manifests the features of the romantic thriller where the master of suspense is exploring the depths in his own abilities that had never been captured on screen before.

In Vertigo, Scottie though initially reluctant to accept the assignment of following Madeleine to save her from her illusions to detect the truth, fails to rescue her when she hurls herself from a church tower. Overwhelmed by guilt and sadness for the woman he has madly fallen in love with, he is duped into believing that the woman (Elster’s wife) has committed suicide to which he is a witness.

It is the villainous Elster who uses Madeleine in his murderous plot to exploit her beauty, charm and sexual allure. She is disguised, her identity altered but she is not entirely a cunning enchantress or simply a manipulator of male desire. She is not represented entirely in negative or perverse terms.

For in Novak, the director projects the femme fatale as a victim and victimiser, and from a feminist perspective this binary of victim/victimiser, originates from a fatal male aggressiveness in the film. In the dual Madeleine/ Judy role, her character is a tragic victim of the men who fashion her into a sexual object.

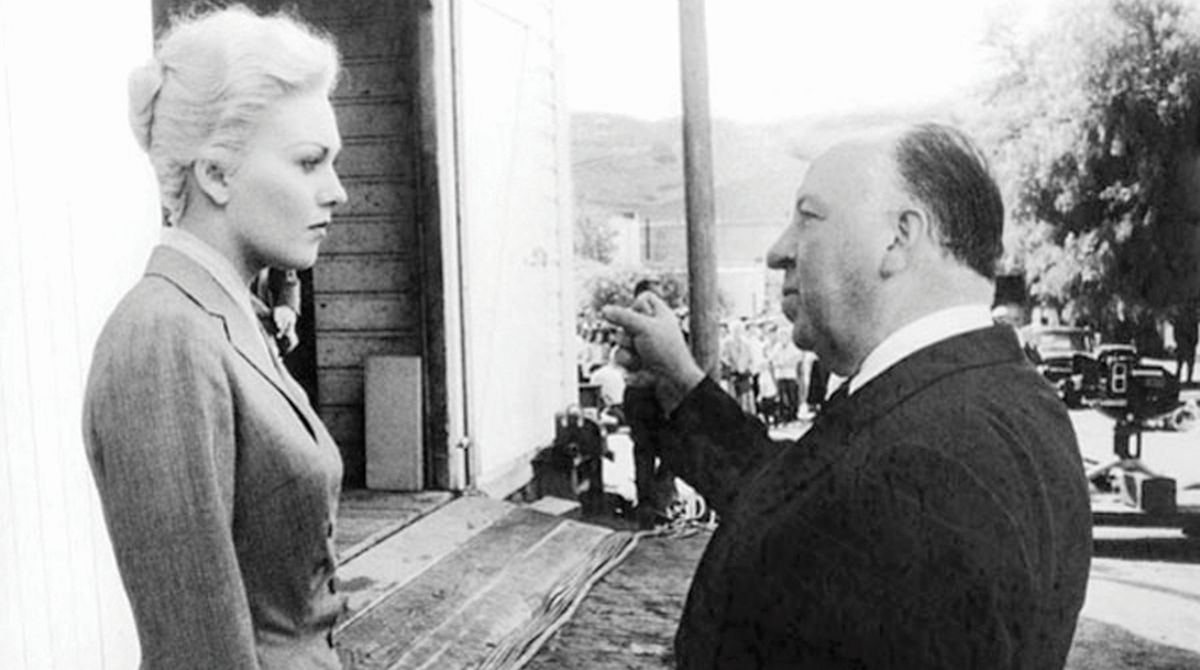

Novak as Madeleine and Judy are brilliant contrasts: Madeleine as well-bred, sophisticated super aristocrat; Judy as warm-hearted, insecure commoner. This dual concept in the character of Novak by Hitchcock has led to significant feminist debates in the film for decades.

For if Madeleine/Judy is here made into an object of deception and desire to which the hero is attracted to and repulsed with, it is also a conflict within the self of the tormented lover.

The complex dualities of Novak’s character, the damsel in distress/scheming seductress is the key to the suspense and success of the film. Scottie who is enraged at the end of the film on realising the double deception tells her, “You played the wife very well, Judy… He made you over, didn’t he, he made you over just as I made you over, only better, not only the clothes and the hair, but the looks and the manner and the words and those beautiful phoney trances… ”

It is Novak’s objectification and fetishisation in the cinema by the male characters and the camera that actually contribute to cinema’s signifiers of voyeuristic pleasure. Madeleine is Scottie’s object of obsessive desire. It is a mystification of female beauty that may be apparent in the film and Bernard Herrmann’s emotionally gripping score creates a sense of haunting, perturbed yearning.

Novak’s position as the mysterious other worldly icon of beauty, was one of the major reasons for the film’s phenomenal success. Francois Truffaut in his interview with Hitchcock in 1962 said to the latter, “I take it, from some of your interviews, that you weren’t too happy with Novak, but I thought she was perfect for the picture… I can assure you that those who like Vertigo like Novak in it. Very few American actresses are quite as carnal on the screen.”

Interestingly then, the film offers a view through a kaleidoscope of genres, challenging the viewer to go beyond a single-genre approach. It playfully features one genre against another; overshadowing one over the other; an approach which promotes creative and productive comparisons to be made across formal generic boundaries.

Hitchcock was perhaps trying to explore the nature and complexities of obsessive love in this film. That love and beauty are associated with something appalling, with the idea of pain, fear, guilt and ultimately the unobtainable.

What actually glued the moviegoer to a film like Vertigo was its ability to body forth and externalise romantic concepts of unattainability, atonement and damnation that were the sources of its appeal and strength. For reasons quite obvious Hitchcock’s glorious masterpiece has progressed from a thriller to a classic love story.

The author is associate professor in English, St Xavier’s University, Kolkata